http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meroitic_script

Meroitic script

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Meroitic

Type: Alphabet

Languages: Meroitic and possibly Old Nubian

Time period: ~200 BC to 600 AD

Parent writing systems: Egyptian hieroglyphs

Demotic script

Meroitic

ISO 15924 code: Mero

Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA

chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key.

History of the Alphabet

Meroitic 3rd c. BC

Complete genealogy

The Meroitic script is an alphabet of Egyptian hieroglyphic and Demotic

origin that was used to write the Meroitic language of the Kingdom of

Meroë by at least c. 200 BC — and possibly also the Nubian language of

the successor Nubian kingdoms, that was later written in a Greek uncial

alphabet which adopted three of the old Meroitic glyphs.

Being primarily alphabetic, the Meroitic script worked in quite a

different way than Egyptian hieroglyphs. Some scholars, e.g. Haarmann,

believe that the Greek alphabet played a role in its development,

primarily because Meroitic had letters for vowels; although in other

respects it did not function much like Greek.

The Meroitic script was essentially alphabetic, but with a default vowel

/a/ assumed unless another vowel was written. A consonant by itself was

indicated by the vowel /e/ (schwa) following the symbol. That is, the

two letters me represented both the syllable /me/ and the consonant /m/

by itself, while the syllable ma was written with one letter, and mi

with two. Some other syllables had special glyphs. In this sense, it is

properly a 'semi-syllabic' script, only vaguely reminiscent of the

Indian abugida alphabets that arose around the same time. Several

syllable-final consonants, such as /n/ and /s/, were often omitted.

There were 23 symbols in total. These included four vowels:

* a (at the beginning of a word only; otherwise /a/ was assumed), e (or

schwa), i, o (or u);

fourteen or so consonants, with an assumed vowel /a/ unless another

vowel was indicated:

* y(a), w(a), b(a), p(a), m(a), n(a), r(a), l(a), ch(a) (perhaps

palatal, as in German ich, or uvular, like Dutch dag), kh(a) (velar, as

in German Bach), k(a), q(a), s(a) or sh(a), d(a);

and several syllables:

* ne or ny(a), se or s(a), te, to, t(a) or ti.

There some is dispute over whether se represented a syllable or a

consonant /s/, distinct from s as /š/; likewise whether ne was a

syllable or a consonant /ñ/; and whether t might have been a syllabic

ti. It has been suggested that the use of syllables instead of

alphabetic letters for some sounds may have been due to the needs of

representing Meroitic dialectical variation within a single unified script.

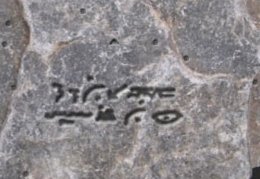

There were two graphic forms of the Meroitic alphabet: a monumental

lapidary form taken from Egyptian hieroglyphs, and a cursive form

derived from demotic. The majority of texts are cursive. Unlike Egyptian

writing, there was a simple one-to-one correspondence between the two

forms of Meroitic, except that in the cursive form, a consonant is

joined in a ligature to a following i.

The direction of writing was from right to left, top to bottom

(cursive); or top to bottom in columns going right to left (hieroglyphic

form). The monumental signs faced toward the beginning of a text, as did

their Egyptian hieroglyphic sources.

There was also a sign of three horizontal or vertical dots used to

divide words or phrases; this was the only punctuation used.

If it was indeed used by the Nubian kingdoms, the Meroitic script would

have been replaced by the Coptic alphabet with the introduction of

Christianity to Nubia in the sixth century CE.

The writing was deciphered in 1909 by Francis Llewellyn Griffith, a

British Egyptologist. However, the language itself is still not fully

understood

...

...